Q&A: Inside the Sketchbook of Ayham Hassan

About to embark on his final year at Central Saint Martins, BA Womenswear student Ayham Hassan reflects on heritage, family and culture through his project exploring traditional family structures in Palestine.

NN: So, can you tell me about this project and why you would consider it to be one of your most meaningful?

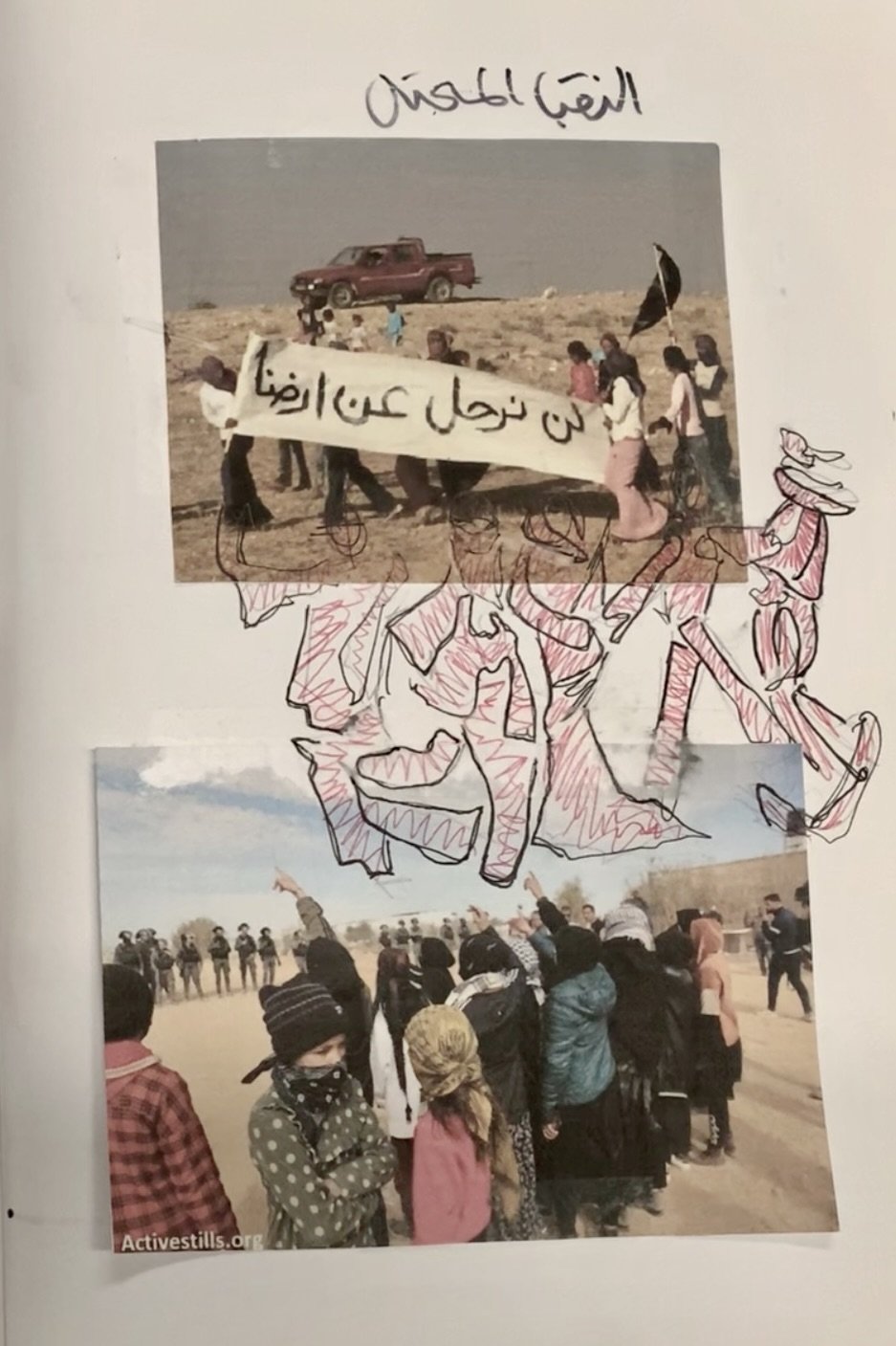

AH: This project was my summer project and the tutors wanted us to focus on Middle Eastern and South Asian references for cutting and draping, which they had never done before. I needed a concept to then be able to focus on the more technical aspects of draping. At that time, I was in Palestine and I was really inspired by this family structure that is very Arab and traditional. The thing that I found most difficult for me as an international student is how individualistic everyone is in London, and how I don’t really see a family unit or something like that amongst my friends. For instance, I talk to my mum every day, to my father and friends - I rarely hear my friends here talking about their family. Growing up, I was very close to my family and we went through a lot together. The idea of family is something very crucial in both my childhood and adult life, it always will be, so I was looking at the family structure in Palestine and the relation of it to land and as an extension of culture. So, I thought: how can I express that through fashion and how is it already documented through fashion? At that time when I was thinking about the concept, we had a lot of family arguments regarding inheritance, which is stupid because the inherited land is documented as being ‘Israeli’, so we can’t use it anyway unless we plant ‘illegally’. So I focused on the idea of land getting soaked and, in Arabic, the idea of ‘ard bur’ (wasteland), a type of land is really hard to build structures on, and doesn’t have plants or anything, it’s neglected. The land that I’m referencing is my grandfather’s, it’s the most beautiful land in the village and this is what my family was fighting about. From this, I started discussing how this land that is already controlled by occupation and restricted and doesn’t have a natural development in terms of growth or water. For example, in winter the land is completely soaked.

NN: That seems like quite a complex concept with lots of roots and layers. Also, just a quick side note - I’ve just noticed that you work from right to left in your sketchbook! That’s so interesting.

AH: Yes, my tutors love it they think it’s so unique but it’s just how I think and work, it’s my sketchbook. Obviously in Arabic we write from right to left, so it’s just how I work. But yes, it was a really complex concept. For example, this is one of the references of how land is connected to my family. So, this concept had so many different aspects and stuff to think about, but it was such a big and important thing to discuss and to be honest, there’s always a reflection of these ideas in my work but not so literally. For this project, I really just wanted to document it all and have it to revisit in the future.

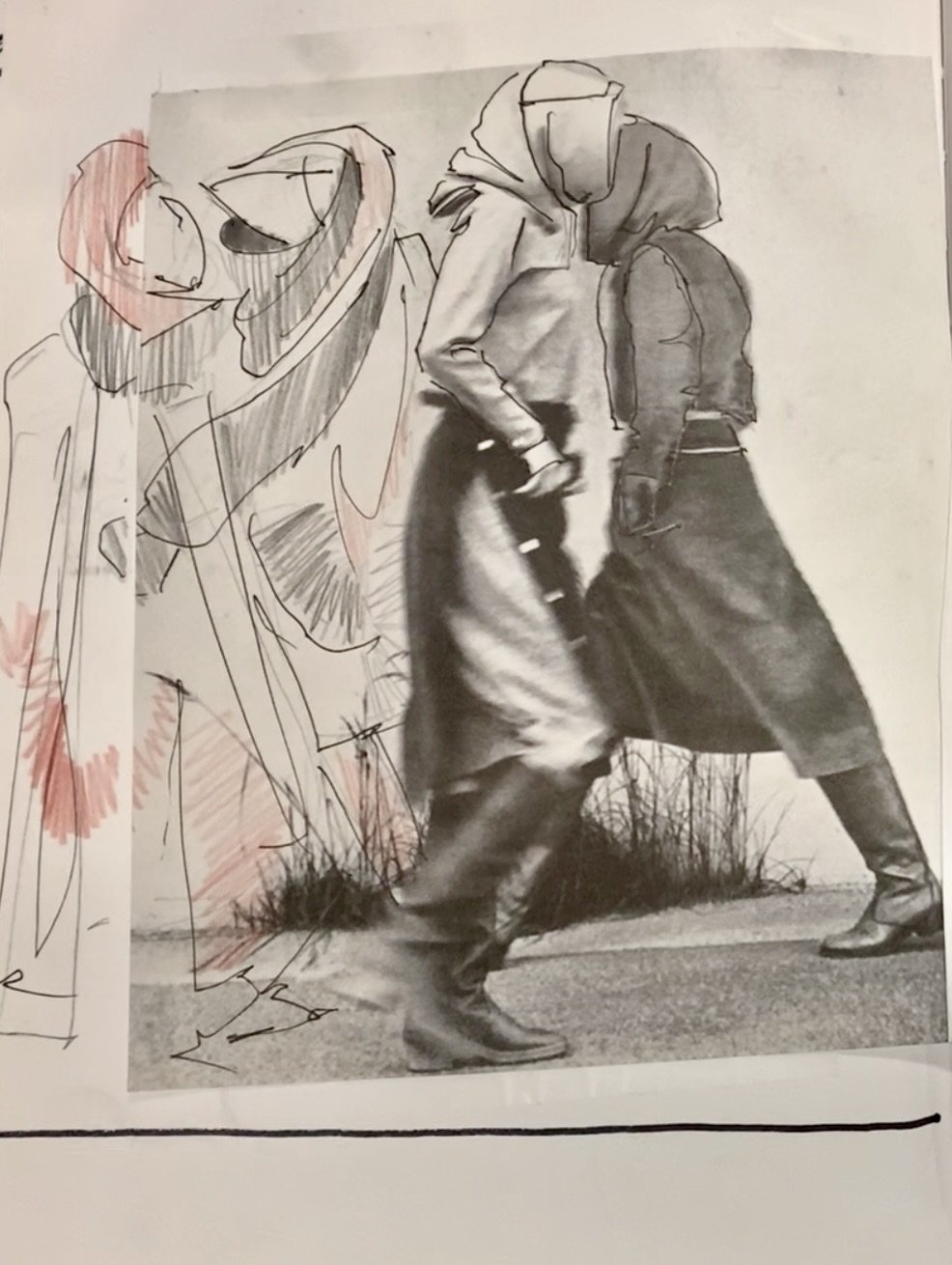

NN: Can you tell me a bit about these drawings and the materials you’ve incorporated in these sketches?

AH: So, this is a palm tree, actually part of a dead palm tree from my brother’s grave. It has such a connection to spirituality and Islam, how people mourn in Palestine and its relation to the body because it’s like planted on top of his grave. When the palm tree died my family was like what’s happening, maybe we’re not connected enough to him, maybe we’re not praying enough, maybe we should do something for him, like have a big meal. That’s part of the customs in Palestine, to always acknowledge the dead and remember them.

NN: I didn’t know about this, so are there set traditions or is it more tailored to the individual?

AH: Yeah, every village really has their own individual customs, every religion has their own customs. For example, in my family, my brother used to really like a certain type of crisps, so my dad bought a load and handed them out to children. Or my mother made rice pudding because my brother used to really like it. So, I was also looking at how people looked next to their land and how the people of Palestine looked. I couldn't find documentation of my village in particular though.

NN: So were you going through archives?

AH: I went through archives, pictures, books, costume books. Other cultures too, like Morocco and Algeria were part of my research. The Bedouin people was interesting to look at because they have a particular relationship with the idea of land. I also referenced garments from Western fashion that I was inspired by, like Issey Miyake. When I thought about this idea I also thought about the idea of marriage, because in my family at least marriage is a really mixed concept, so I looked at different marriage ceremonies. This project too was technically referencing garments, so Issey Miyake was a good reference for organic shapes. The references were so diverse, from Miyake, to a woman in Algeria, then to Bedouin tribes. Textures were also a big part of this too.

NN: I noticed, through the whole sketchbook there’s been pieces of metal and mesh.

AH: The sketchbook definitely goes through a bit of a journey. I start very personal and then it becomes more general. Like at one point I looked at Palestinian costume and I felt a lot of energy from them, and then I was looking at different places in Palestine that I’m not familiar with because of the occupation.

NN: It looks like you’re also quite interested in different technical aspects, like pleating and big forms, also lots of textures.

AH: Yes, I definitely am. I love a lot of fabrics - a lot of fabrics - and a lot of draping. I like a form that doesn’t have very defined details, like ‘this is a pocket’. Also, in this project I went a bit random at time with references.

NN: Do you think this has anything to do with previous ideas you’ve discussed, like the concepts of freedom, spirituality and expression?

AH: Yes, in one way or another. I think so, because with this idea of my brother, at the end of the day we’ll all be stripped down and go back to the land so the more fabrics you have the more you’re symbolising the idea of wanting to live. I love draping though, I find it can make something feel very abstract. This collection for me was very inspiring.

NN: You also have a contemporary reference here with Elyanna.

AH: Yes Elyanna! At that time, I was really inspired by a fabric, I was actually obsessed that it was both silk and pleated Indian silk from Shepard’s Bush. I bought it and kept it and randomly thought about it for this project, but it also really reminded me of Elyanna. As you can see in this sketchbook, I was very emotional, and my work was really full of energy. Sometimes tutors will ask me how I can sketch a silhouette so quickly, but it’s just an energy that I feel and the vibe that’s in my mind. The drawing is just a reflection